I recently received a message from Fiona Whitehead from this publication who happened to stumble over the 1956 Le Rosey yearbook which included an article entitled a “Vacation to Tragedy” that described a trip that I had taken to Hungary during the revolution in the Fall of 1956. Fiona asked three questions “Are you still alive? Was it true? What else happened to you?”

I am alive 45 years later, the story was true. A life has happened to me as it has happened to all of my classmates. The very phenomenon of being 62 years old guarantees that we have had a front row seat watching and occasionally participating in History as it whirled on by.

My week in Hungary changed my life. I had been at Le Rosey for less than two months, I had been in Europe once before in 1954 when I lived in the village of Tourtour in Provence for two months. I had failed French at Andover, an American prep school, and when confronted with summer school or living with my French teacher mother, I elected to go to France. The village could not understand where I came from, and concluded that I was an orphan. When my French improved sufficiently to discover that I was an orphan, I realized that everyone had been so kind to me as an orphan that it would be cruel to disillusion them with the reality that my parents were alive and well. I remained an orphan. I had a wonderful summer.

I arrived at Le Rosey from a small town in America (Williamstown Mass., 5,000 people), immature for my age, inept at soccer, devoid of social graces, speaking English and small boy French, a language that did not work well at big boy Le Rosey. But I had a dream of what I wanted to be. I wanted to see the World and I wanted to see it through the lens of a camera. Long-term (ten years), I hoped that I might become a diplomat and change the World that I had seen.

In contrast to most of my classmates, I had had a job. For three months during the summer of 1956 I was a photographer for the Berkshire Evening Eagle, an award winning newspaper in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. I took pictures of local news, weddings and other disasters. Two or three of my photos were sold to United Press International (UPI). I took underwater pictures that were published in the Eagle five months before the first underwater pictures showed up in the National Geographic.

In late October 1956 the Hungarian Revolution broke out. I decided that there would never be another revolution and that I had to be there. I can no longer remember what excuse I used to get permission to leave the school for the weekend. My parents were in Europe and I probably lied that I was going to be with them. I told my roommate that I was going to Budapest and that if I did not make it back, that that was where I would be. I had no sense of risk, then or later. Teenagers and journalists believe that they are immortal.

I left Rolle on a Friday afternoon to fly to Vienna, stayed overnight in the UPI office and set out to hitchhike to Budapest the following morning. I crossed the border without documents and found a ride in a car that had been rented by a Hungarian lady living in London, a resistance leader who had been in Austria looking for support, and a trunk full of plasma. It was All Saints Eve and three or four graveyards on the way along the road were illuminated with candles. The graveyards alternated with Russian tank encampments illuminated with bonfires.

I left Rolle on a Friday afternoon to fly to Vienna, stayed overnight in the UPI office and set out to hitchhike to Budapest the following morning. I crossed the border without documents and found a ride in a car that had been rented by a Hungarian lady living in London, a resistance leader who had been in Austria looking for support, and a trunk full of plasma. It was All Saints Eve and three or four graveyards on the way along the road were illuminated with candles. The graveyards alternated with Russian tank encampments illuminated with bonfires.We arrived in Budapest late in the evening at the apartment of the Hungarian lady’s sister whose husband worked for a lamp factory in Pest. The parents said goodbye to two preteen children who would be taken back to England. The parents clearly did not know if they would see them again. We dropped off the plasma at the central hospital. The car went back to Austria. I stayed. It was the beginning of my Le Rosey education. The world took on dimensions and consequences that I did not know existed.

I was three days in Budapest before the Russians returned. I still remember the details as if it were a film seared into my mind. I am surprised today how much I remember. In the midst of it all I remember humor, I remember being asked where the Americans were and having no answer. I remember kind people who somehow cared about a stranger in the midst of a crisis.

When the Russians returned I joined a convoy that intended to cross the Austrian border. We were sent back to Mosen Magyarovar, a Hungarian town about fifteen kilometers from the border. We were in a gymnasium surrounded by Russian tanks with an armed Russian in every room. There were 10 journalists and about 100 diplomats and other refugees trying to get to Austria.

A humorous incident developed. I wanted to be with the journalists, I did not want to be a refugee. I approached the group of journalists who were sitting around an old Hungarian porcelain stove. They were drinking Scotch. Ten years later one of the journalists, Frank Donghi from NBC news, wrote me a letter wondering if I was the same person that he had met that day. He remembered my opening line,

“I am a minor, but I am a minor in a major situation and I need a drink.”

He added if you are the person who said that I would like to see you again. The journalists said that I could have anything I wanted if I got the fire started. Later, another of the journalists occupying the stove, Catherine Clark of INS, wrote a story about a Young American who had started a room-size Hungarian stove under the barrels of Russian guns to keep refugee children from freezing as the snow fell outside the window. I wanted to join the journalist club, the price of admission was starting the stove, the reward was the Scotch. I was no longer a kid stuck in a bad situation. I was a journalist. The chilly children had little to do with my efforts.

A few days later when I got out of Hungary, I sold my story to AP and the photos to UPI. I was on my way as a journalist. I was also on my way back to Le Rosey having disappeared for more than a week. My fate was uncertain at best. In any American prep school I would have been thrown out. Le Rosey was different and I can look back at my life and say that the tipping point, that critical moment in all of our lives where circumstances could have gone either way, fortunately went my way. Louis Johannot did not throw me out, many years later he told me that he respected what I had done. He treated me the way all 17-18 year old kids want to be treated, with humor, irony, and a sense that we were all works in transition. Kids en route to being adults. He treated me as a kid who had successfully pulled off an adult achievement. It was for me the tipping point. I was and am grateful.

I continued to be a journalist. After being held by the Russians at gunpoint for three days, I thought that it would be helpful to speak Russian in the future. Le Rosey obliged by providing a Spanish lady who spoke Russian, who taught me in French, with the aid of an English textbook, the Russian language. This did not work. Yale University tried as well but it took an intensive summer course at Yale to get me through the first year.

In 1959 I showed up in Moscow and got a job with UPI’S legendary bureau chief, Henry Shapiro. My job was to keep the UPI White House photographer from getting lost; and taking backup pictures when he did. I also ran the lab and took the pictures to the central telegraph office. He got lost a lot and they used my pictures, including a portrait of Khruschev in the cockpit of Nixon’s Boeing 707. The photo was used in the centerfold of Look magazine and hung in their NY lobby for 5 years.

The following year I was hired to go with Eisenhower to Russia. The trip was canceled because an American U2 was shot down over Russia. I sent a telegram to the Prime Minister of Mongolia. He sent me a visa, and my 20 year old wife and I were the third and fourth Americans in Outer Mongolia after World War II. I interviewed Yumshagin Tsedenbal, the Prime Minister, and generally continued a pattern of unrestrained curiosity verging on delinquency.

The following year I was hired to go with Eisenhower to Russia. The trip was canceled because an American U2 was shot down over Russia. I sent a telegram to the Prime Minister of Mongolia. He sent me a visa, and my 20 year old wife and I were the third and fourth Americans in Outer Mongolia after World War II. I interviewed Yumshagin Tsedenbal, the Prime Minister, and generally continued a pattern of unrestrained curiosity verging on delinquency.During the ensuing years I spent 14 years involved with agriculture in Iran. The 27,000 tons of refrigeration capacity we built was lost to the Ayatollah but still runs. My Iranian partner’s son, Nader Mousavizadeh, went to Harvard, won a Rhodes Scholarship and now works with Kofi Annan at the UN on the problems of the Middle East and Africa.

Along the way I spent 30 years as Chairman of National Semiconductor. When I started we made 3,000,000 transistors for $1. When I left we put 3,000,000 transistors on a $1 chip and our sales were over $2 Billion. I had a front row seat in an industry that changed the world. I was still curious. I have been involved in lots of other businesses including Aston Martin Lagonda where I was Chairman from 1975- 79. I even lost a Congressional race in New York City against Ed Koch in 1970. Some of it worked, most of it didn’t

Back to Le Rosey and the tipping point. The school then and now gets kids from a variety of backgrounds; generally with substantial wealth aristocratically arrived at or recently blundered into. Most of the stuff we arrive with is ignored by the school and by our peers. We were and are still kids and in the last two or three years, we were and are still desperately attempting to escape from being kids to become adults. I can assure you that after 40 plus years of adulthood, it is highly overrated.

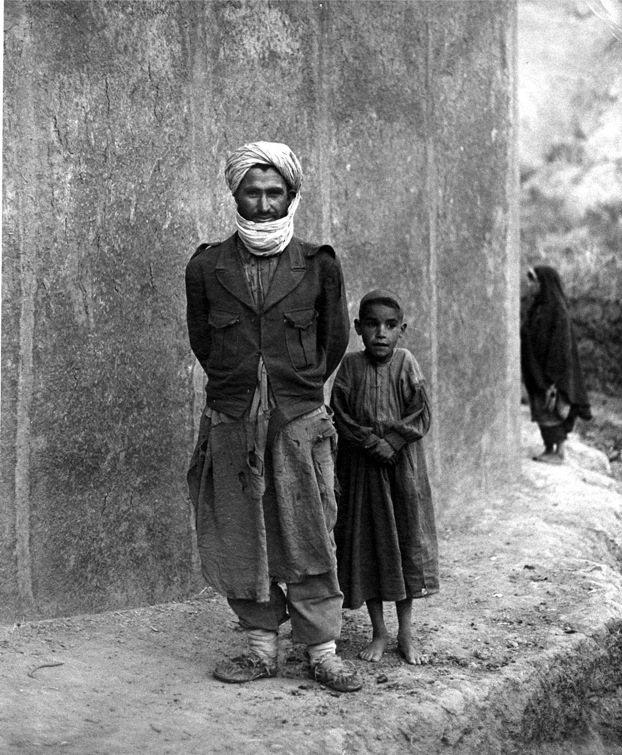

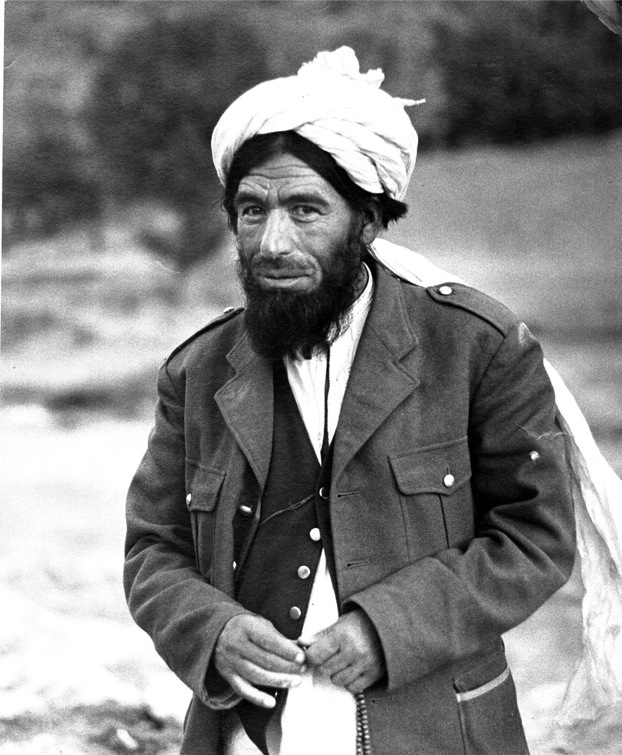

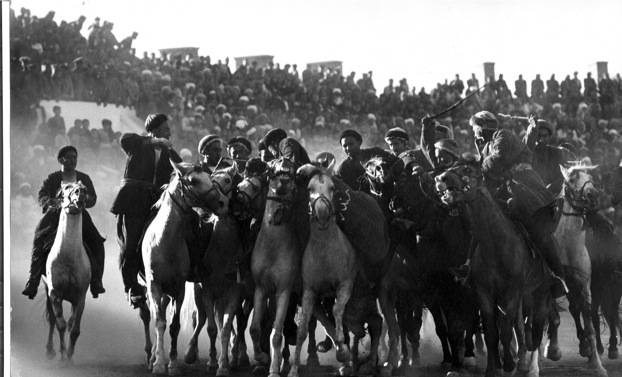

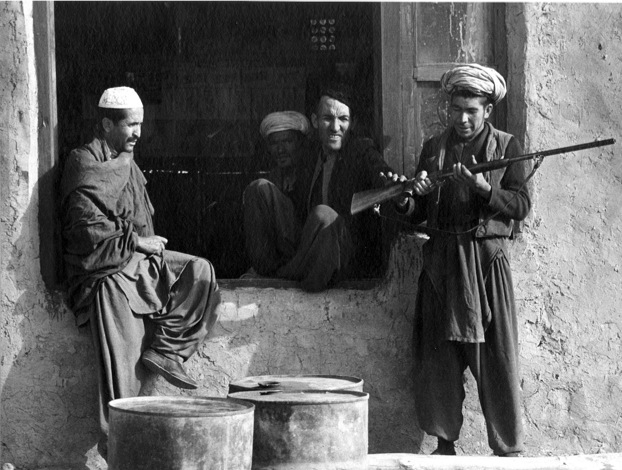

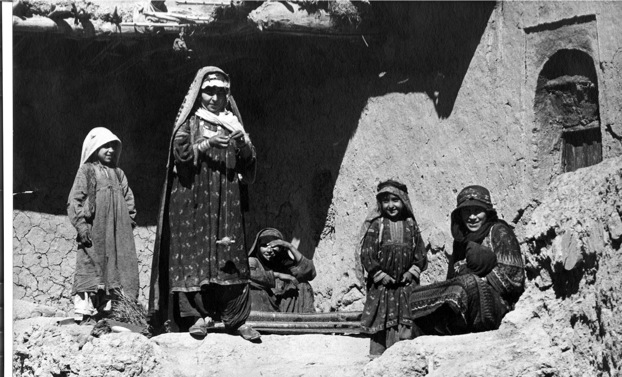

Fifteen years after Hungary I went to Afghanistan. My wife suggested we make the trip. She loved Iran and wanted to find out what it must have looked like fifty years before. We had four boys at home under 10. We left on a one month trip of which ten days were in Afghanistan. There were three of us and a driver. The Farsi speaking American I worked with in Iran wanted to turn back when we reached Bahmian. It appeared too risky. The dirt road ahead through the central mountains of Afghanistan crossed over 30 peaks of 3,000 meters and 4 of 4,000 meters. It was a truck and a half wide. The goal was the Minaret of Jam. It had been discovered by the French in 1957. The few hundred villagers who lived at its base for the previous thousand years did not know that they had not been discovered.

My friend stayed with us and we completed the trip, driving back to Kabul through Kandahar. I remember Afghanistan with respect, awe and a kind of love. The people had almost nothing, but would share everything they had with a warmth not found in the civilized world. I could have saved dozens of children eyesight with a few tubes of antibiotics that I did not have the intelligence to carry. I left feeling diminished by my rented Land Rover and my conspicuous assets. I left feeling enriched by what I had found.

Today Afghanistan is much in the news. They have been plagued by the Russians, by four years of drought, and the fanaticism of a branch of their own Islamic beliefs, financed by foreigners. I look at the photos I took in 1971, and the articles I now read, and realize that I am still the curious human being that Le Rosey allowed to flourish. I cannot look at the news without remembering that in Hungary the freedom fighters were not trying to kill Russian civilians but the Russian army. The Russian army was trying to kill freedom fighters but not Hungarian civilians. Thousands were killed, but they were fighting by the old rules. I live in New York, the rules after September 11 have changed.

Today Afghanistan is much in the news. They have been plagued by the Russians, by four years of drought, and the fanaticism of a branch of their own Islamic beliefs, financed by foreigners. I look at the photos I took in 1971, and the articles I now read, and realize that I am still the curious human being that Le Rosey allowed to flourish. I cannot look at the news without remembering that in Hungary the freedom fighters were not trying to kill Russian civilians but the Russian army. The Russian army was trying to kill freedom fighters but not Hungarian civilians. Thousands were killed, but they were fighting by the old rules. I live in New York, the rules after September 11 have changed.All of us who have been to Le Rosey belong to the 21st century elite, along with less than a billion others for whom this is the world that we and our children live in. Another five plus billion people live in a different world. They share the same planet, but they have had their traditions, their ecology, and their world destroyed and have a future that is ill-defined at best. There are no Islamic Mercedes or Buddhist Disneylands.

Le Rosey, and the life that I have had since, have left me with a belief that we should try to understand both worlds. I would recommend to all teenagers that they not only struggle to get into college, struggle to get into graduate school, struggle to join a successful firm, struggle to create a family and struggle towards family security for themselves and their family. Take some time off, as early in your life as possible. There is more than one world out there. You were born by accident but you have a role to play. Take risks, search for your role in this world and live it.