The following is an account of Peter Sprague’s history with the Aston Martin Car Company, By Peter Sprague, originally reproduced in print as a 3-part series in the Member Magazine of the Aston Martin Owner’s Club of North America.

SWIFT RUNNING

by Peter Sprague

Prologue

On Monday, December 30, 1974 people all over England went back to work after their Christmas break. In Newport Pagnell, a small town about an hour northwest of London, over 500 men and women went to work at Aston Martin Lagonda, the town’s largest employer. Some were able to walk to work; many had worked there for decades. There was a pattern to their daily lives. This Monday was different—the factory was locked.

There had been no real warning. Things had not gone well for the previous few years; ownership had changed and seemed to have no direction. Company assets appeared to evaporate along with the sports field in back that had been taken away from the local cricket teams and sold to developers. Things had emerged in a darker shade of gray. Now they looked completely black. Everyone milled around the closed building and compared rumors and misinformation.

The name Aston Martin conjures up images of elegance and power. These images are not supported by the factory visage in Newport Pagnell; a hodgepodge of brick additions sprawled inelegantly around “Sunnyside,” the headquarters building, a dilapidated small faux Tudor house of modest pretensions built for Mr. Salmons early in the 19th century.

An announcement was posted on a few doors that told everyone to meet at the cinema in town the next morning. Ironically the theater was owned by the daughter of one of the Salmons family descendents and was one of the last private movie theatres in England. (It is now part of a shopping block.)

At the meeting, marketing manager Fred Hartley welcomed everyone and introduced Michael Clark. The company was pronounced bankrupt and Michael was the receiver. The creditors were in control. The terms of redundancy were explained. In most cases there were no jobs to go back to. The Service Department would stay open but the factory would remain locked.

Craftsmen had been making wheeled vehicles in Newport Pagnell since 1820. Before Aston Martin there was Tickfords, who made carriages, and then later bespoke automobile bodies, and before Tickfords there was Salmons who made bread wagons and hearses. A few of the men and women at the cinema that day had family who had worked at the same location for four generations. The pubs must have been busy that gloomy Monday evening.

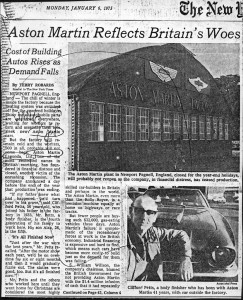

The next day the press announced to the world that Aston Martin was bankrupt and closed. There were few places so obscure that the news was not heard and repeated. James Bond’s car had been finally destroyed by the villains of commerce. Ten thousand Aston Martin owners wondered about the future of their cars. People who had owned Astons in the past were given to reminiscing. People who had dreamed of owning a new Aston in the future knew that there would be no new Astons. Another famous automobile company had died.

That evening Walter Cronkite delivered a eulogy for Aston Martin on The CBS Evening News wearing a black tie. It has been reported that he rarely did this for man or beast.

I am sure that there was much in the news that day to get upset about. There usually is. But Aston’s demise really bothered me.

In 1962 I had bought a used 1960 DB4. The ads said it could go from 0 to100 and back to 0 in less than 26 seconds. It could and did. It became my wife Tjasa’s car. At the time I had an Alfa Romeo Spyder that eventually wore out. When we moved to New York in 1962 with our son Carl we sold the Alfa and the Aston was our only transportation. Son Steven soon arrived and we would pile the kids in the back, on a foam covered plywood panel, where they rattled around in pre-child seat bliss. Finally, sons Kevin and Michael arrived and we bought a larger car. But the Aston remained in the family. We still had the car in 1974.

I had been to the factory in the early 60s with my future brother in law and again in the late 60s when we shipped the DB4 to Newport Pagnell to acquire a sunroof. I had wanted to take a factory tour but was not important enough to get one. I still had a sense of the people and the craftsmanship from my visits, a feeling that anyone who visited “the Works” in those days must have felt. It was far from Detroit mass production; far from the microelectronics that I was involved with—it was a special place that brought to life prewar photographs of a different world.

I emerged from the tub frustrated by Aston’s demise, and announced the news to my family in the kitchen with the comment, “Why did that have to happen?” Off and on over the next two days we kept returning to the question of why Aston had to go out of business. Finally Tjasa brought my complaining into focus. “Why don’t you do something about it?” I had been up to my neck in hot water when I read the news. I did not realize that that was just the beginning.

I turned to a young friend who was staying with us, Morris Hollowell, and said that if he could get me the name and telephone number of the managing director in England I would call him up and possibly go over to England after the weekend. Morris tracked down Rex Woodgate, who represented Aston in the US. Rex volunteered the name of Charles Warden and his phone number. I called Charles and briefly introduced myself. We agreed that I would come over after the weekend. I reserved a room at the Dorchester, flew over on Sunday and was met by a V8 from the factory on Monday morning.

I was the perfect person to get involved in Aston Martin. I was 35 years old. I knew nothing about any aspect of the car business. I had never been inside the factory or met any Aston luminaries other than Rex Woodgate. I was not as impressed as I should have been that the British economy was in terrible shape, The Financial Times stock index was at 176—today it is over 4,000. There were even discussions of a possible intervention by the World Bank. Things were grim, but I was cheerful—I truly did not understand the situation.

On the positive side I had had some experience with startups and troubled companies. At the ripe age of 26 I became Chairman of National Semiconductor when the company was coming out of receivership. By 1970 National was on the NYSE. I had learned entrepreneurship by starting a chicken farm in Iran with Iranian, Lebanese and American partners. By 1975 we had 27,000 tons of cold storage capacity in Tehran and Khoramshar. Instead of raising 3,000,000 chickens it was easier to import 100,000,000 frozen chickens from Europe. I had also become involved in a number of other enterprises along the way, both failures and successes. But no car companies, large or small.

My education consisted of political science at Yale and MIT and economics at Columbia. My first job at age 17 was as a photographer for The Berkshire Evening Eagle in Pittsfield, Mass. I continued as a photographer with UPI in Russia in 1959 covering the ‘kitchen debates’ of Khrushchev and Nixon. Tjasa and I visited Outer Mongolia for UPI in 1960. We were the third and fourth Americans to make the trip after WWII. We had been preceded by Owen Lattimore and Harrison Salisbury.

In 1970 I lost a Congressional race against Ed Koch in NY. A less than perfect background for the upcoming events at Aston. I did have a lot of energy. I did not have enough money to buy a car company.

It is possible that I would not have become seriously involved with Aston if I had not been ensnared by the British press. When I arrived late in the morning of January 6, 1975 in Newport Pagnell, I was astonished to find 30 – 40 reporters and photographers elbowing each other in an enthusiastic scrum around the V8 the company had sent to pick me up. One question that was asked was “Who are you?” I announced that I wasn’t anybody. That really raised the interest level. Charles Warden desperately wanted to keep alive the possibility that Aston could be saved. It seems that I was the first to show interest. He had called members of the press and announced that “an American” was coming over to save the company. I was a thin straw to grasp.

Geoff Courtney, then employed as motoring correspondent was part of the scrum. Before the end of the year he would join Aston as internal PR and part of the marketing team.

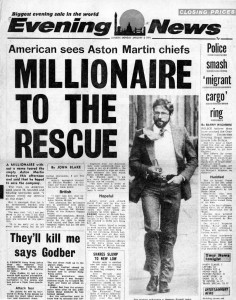

It appears in retrospect that nothing of any importance occurred anywhere in England, or perhaps even in the world at large on Monday, January 6, 1975. There being no other news, my visit to Aston made the front page of a wide variety of newspapers including The Evening News, who trumpeted a Page One banner headline “Millionaire to the Rescue.” The article began, “A millionaire without a name toured the Aston Martin factory this afternoon and said that he hoped to save the company. The man, an American aged about 35, bearded and wearing spectacles said ‘I cannot reveal my identity at this time.’ I did not actually say that, but that’s the quote.

There was a dramatic picture on the front page of me clutching a pipe, with my tie in the wind, looking rumpled. If they didn’t know who I was it is curious to know how they concluded that I must have had a million of something. They did not specify the currency.

The following day the press knew my name. I was in fact not anyone in particular. I decided I could not leave England after having raised everyone’s expectations without taking a thorough look. I felt then, as I do now, that you do not play with people’s emotions lightly. Aston Martin Lagonda meant a great deal to a wide variety of people. From owners to dreamers, from craftsman at the works to suppliers, from small boys to their older equivalents, Aston was important to a wide cross section of people. As a result it became important to me.

After we escaped from the press, Charles Warden took me for a walk through the factory. It was an experience that I still vividly remember. A week before everything had stopped without warning. We started with the raw material, racks of sheet metal and leather and parts, walked down the production line and I imagined the process of a car coming to life. Except there was no life, only an eerie quiet with a background aroma of leather and oiled metal. It was clear that I never would see Astons being built, only a graveyard of unresolved craftsmanship. I wanted to see it come alive again. I did not know how difficult it would be or how long it would take, but I became emotionally hooked.

In addition I was curious. Curiosity can get you in a lot of trouble. I have always been fascinated by what might be on the other side of a hill. Aston was truly a curious hill.

I went back to London feeling overwhelmed. The following morning I read all the clippings and realized that I had been maneuvered into the center of a circle of attention that I had not expected.

I determined that I would put in a month to better understand what had gone wrong and what could be done. If it appeared to be impossible, I would have a press conference, assemble some serious looking flip charts and explain what I had concluded. I trusted that people would forgive me for raising their hopes.

Facts were hard to come by. Aston Martin Lagonda had been acquired by Company Developments Ltd. William Willson, the principal of Company Developments, had installed a receiver (Michael Clark) who I later learned had been involved with him in a furniture business. They did not seem too happy about my arrival and inquiries. Most of my time in Newport Pagnell was spent in an uncomfortable wooden chair in a small office in the unprepossessing headquarters building in front of the factory. The receivers’ frugality on behalf of the creditors included not providing heat. It was January and damply chilly. They could at least have installed a heater with a coin slot of the Dickensian variety. I would have gladly paid up.

Aston’s employees were at least able to liberate their tools. Newport Pagnell is a tight community. Everyone knew everyone and most of Aston’s former employees lived in town. The night watchmen turned a blind eye and tools and tea mugs migrated to their rightful owners. Jack Hilliam, one of the lead panel beaters, rescued his hand crafted “flatters, chasers, flippers, tuckers and shrinker fitters” among his other tools.

A number of Aston craftsmen found jobs at Rolls Royce in Willesden, North London that involved a long bus ride on buses that Rolls Royce sent daily to Newport Pagnell. Jack Hilliam recalls that “we were all in a state of shock and we were really down working at Rolls Royce. Their panel beaters had been on strike for a long time, but we AML people were treated like Gods. I would finish our weeks’ work by Wednesday—I couldn’t work any slower! They did a good job on the Phantoms, but there was 90 pounds of lead filler on the Camargues.”

I found a room at a motel off exit 14 of the M1 and quickly discovered why it lived up to its Egon Ronay Guide rating as one of the worst motels in England. I moved to the Swan Revived, Hotel and Pub, in Newport Pagnell, next to a Church whose bell tower started raucously chiming the hour at 5am every morning.

William Willson showed up occasionally, wearing a yellow windcheater and orange socks, or perhaps it was the other way around. I later learned that in the dying days of Aston, Wilson had spent a week or two in Japan enjoying the £1000 a day Presidential suite at the Okura with a butler and limousine patiently waiting around the clock. The subsequent bill was sent to the Japanese importer and contributed to his later bankruptcy. Photos of Willson enjoying the night life of Tokyo somehow had found their way to the factory floor a few days before its closing. That had not inspired the work force. If he had been a more impressive executive I might have been discouraged.

There were obviously a lot of assets: 110,000 sq. ft. of manufacturing, 14 acres of land and a new service center that had achieved a profit of £250,000 a year. Over a million and half pounds Sterling of parts, £760,000 of work in progress and 60 completed or nearly completed cars at the factory or in the US.

I went looking for partners. Almost every day some new consortium or individual would come forward, usually through a press release, with a stated interest in doing something. I was open to all possibilities including bowing out gracefully if I could find someone determined to go ahead on their own. I would not have been unhappy if someone else brought the factory to life. I could go home and buy a car from the new owners.

The basic underlying problem was that it appeared Aston Martin Lagonda had never in its history made a profit. One of my favorite David Brown stories, possibly apocryphal, was that when approached at a cocktail party by a gentleman who asked if Brown could arrange for him to buy a car directly from the factory, at factory cost, the reply was “certainly—that will be two thousand pounds over retail.” Much later on, Alan Curtis and I often used the same response in similar circumstances. In addition, I did not have a team with whom I could develop a plan. The previous management was scattered to the winds. Aston employees were on the dole looking for work, the panel beaters were temporarily at Rolls Royce enjoying a two hour round trip bus ride from Newport Pagnell. The factory was regularly visited by one elderly gentleman who was trying to keep the machines oiled and functional. I would occasionally walk through the cold and empty buildings and these solitary walks still inspired me to keep going.

It was difficult to answer the question: “If others have failed why do you believe you can succeed?” I could not find a convincing reason why it could not be done. I needed enthusiastic support. I found it in the person of George Minden. George was the Aston distributor for Canada. He was a complete and knowledgeable enthusiast of Astons, Bentleys, etc. He had lived in Toronto but had recently moved to England with his wife and two young daughters. In Toronto he had an elegant boutique Hotel, The Windsor Arms, with a wonderful restaurant—Three Small Rooms.

George had a specific problem. A few weeks before Aston went into receivership he had purchased 6 new Aston V8s from the factory. He was given no warning of the impending financial problems. He knew that he would have major problems selling the cars if the company was permanently going out of business. He called his own press conference in Canada to announce that he was interested in putting a consortium together to save the company. His news conference received wide coverage. I read about it in The International Herald Tribune. I called him up to tell him that I was glad that he was going to save the company and offered to support his efforts. George was surprised by the interest that his press conference had stirred up. He was also surprised by my call. He did not intend to save the company on his own. We met in London at the Dorchester and agreed to work together.

I flew up to Toronto from NY and met with the head of George’s operations, John Cox, a cockney former welterweight boxer who added his enthusiasm and convinced me that we could do a better job marketing the cars.

We stayed in regular touch after our first meeting. I had someone whom I could talk to who did not feel that my goals were completely quixotic. Without him I might have simply fallen off my white horse from frustration and exhaustion. George said that he would invest working capital if we were able to acquire the assets from the receiver. We agreed that we needed a lawyer and an accountant. As an American I believed that the lawyer would be more important and picked a solicitor at Slaughter and May. George engaged Philip Sober, the managing partner of Stoy, Hayward. Philip immediately became a critical part of the story; his counsel and support were invaluable. He stayed involved with Aston through to the early years of Ford’s ownership. I could not have succeeded without him and he remains a close friend to this day. The lawyers remained involved through the closing of the purchase transaction. I learned that accountants held the high ground as advisors in England, or at least they did in the decade of the 70s.

I had well over a hundred meetings during the first six months of 1975 in pursuit of cash or partners in an effort to restart the company. George Minden was at many of the meetings. We developed a “dog and pony show.” We had a running discussion about “who was the dog and who was the pony?”

I met with investment bankers in NY and London. With dozens of individuals and groups, from Jarvis Astaire the gambling impresario, to Aston Martin Owners Club enthusiasts and many who seemed only to be interested in tagging along for publicity that involvement in Aston always seemed to engender. There were always groups of Middle Easterners on the horizon, where they remained. There were no camels toting bags of gold.

I was searching for “yes.” I rarely got a “no,” people usually just drifted away.

I did have two meetings with Jacob Rothschild. After the first, his team looked into the situation and then he called for the second. He said that he appreciated what I was doing, and that it was unlikely that the company could be profitable, however if I bought the company and then sold off the assets it would probably be a very profitable transaction. He said that he would not want to do that and doubted that I would. He declined to become involved. I appreciated his candor and the fact that he had done the analysis and concluded with a polite “no.” Most of the people I talked with seemed to primarily enjoy the “talk.”

The major problem that I faced was the fact that William Willson, Company Developments, and their receiver refused to set a price for the assets, avoided negotiations and seemed to have little interest in reaching a conclusion. Willson had stated on numerous occasions that his goal was to help bring the company back to life. He eventually lived up to that commitment. But it took awhile.

My own finances were improving. My major asset, National Semiconductor stock, rose significantly during the spring of 1975. I went to National’s bankers, The Bank of America, where I met a courageous banker who agreed to loan me £600,000 against the 60 mostly completed cars. 19 of those cars were at the company owned distributor in King of Prussia, Pennsylvania. I went down for a visit with Rex Woodgate and took inventory. Rex said that there were 23 cars. I counted 19. He reiterated 23. I recounted 19. Rex commented, “It feels like 23 to me.” We finally agreed there were 19 and I bought one of them, a dark green V8. Rex was a superb mechanic and a good car salesman but clearly should not give up his day job to become an accountant. I was becoming more committed. A few of my saner friends thought that I should be.

In late May I decided that I would try to purchase the assets on my own, and then sort out the situation afterwards.

I managed to get myself invited to William Willson’s home in the country for a weekend. I had heard that he was planning to sell the company to an American company called Robert Carl Associates. My assistant, Carla, managed to track them down to a Detroitbased industrial liquidator who had created Robert Carl Associates for the occasion. I called a few of the journalists I had met during the course of the Spring, gave them Willson’s home telephone number and suggested they call during the weekend and inquire why he was selling the company to a liquidating firm after his promises to help put Aston back in business. As part of my diplomacy I let Mr. Willson beat me at ping-pong. At least that is the way I like to remember it. By the end of the weekend we had agreed on a price he would support, he even volunteered to help with the financing by providing a short-term loan. I do not now remember the terms of the loan or whether we used it.

There was £300,000 in the receivers account, I had £600,000 committed by the Bank of America, and I agreed to provide an additional £170,000 for a total of £1,070,000. That was my offer and after weeks of discussion they accepted it. Michael Clark the receiver announced that the offer was “inadequate” and referred to us as the “American Circus” but did grant that we had been “tenacious.” There were no other bidders and no one else had come forward during the previous six months. Effectively I was buying all the assets of Aston Martin without liabilities for £170,000 cash. I could have kept the name and the service business and sold off the assets for a few million pounds. William Willson could have done the same. We both agreed that the company should stay in business.

We now had to arrange a closing. There were a few more steps. Philip Sober developed a checklist. As a foreigner buying a British company I needed approval from the Bank of England. We went to an intimidating large gray stone building. The serious functionary at the other side of the desk had his own checklist. When we got to National Defense implications, he inquired with a smile if we intended to keep the James Bond tradition and add machine guns. We agreed that I would come back for special permission if machine guns were required. The Bank of England signed off on the deal.

Because we needed a company with which to buy the assets, Slaughter and May produced TruShelfCo #23. We changed the name to Aston Martin Lagonda (1975) LTD after we acquired the assets. Five years later we were allowed to drop the (1975). I needed an English shareholder for some of the transactions. A trustworthy friend of long standing, Jan Dauman, became that shareholder and I believe for a very brief time became the owner of Aston Martin, or at least a part of it.

While the paper was being shuffled in late May, I made one of many trips home. I returned on the QE2 with Tjasa and my four sons aged 5 to 14 and our friend Morris Hallowell. After a couple of nights at the Dorchester, my family and Morris went off to Bath for the weekend. My youngest son Michael was disappointed by Wales—there weren’t any (whales). He also concluded, after counting the 26 doors in our suite—closets etc.—that this explained the reason the hotel was call the Dorchester. I went to Birmingham to complete the purchase.

I arrived for the closing on a rainy Friday afternoon in a parking lot outside an office block in Sollihull. For reasons I never understood we could not meet indoors where some enterprise of William Willson’s had an office.

So William Willson, Michael Clark, my lawyer, his assistant and I stood in the rain exchanging documents. All of a sudden my attorney blurted out. “We can’t have a closing.” I was expecting difficulties from the other side, not from my attorney. It seems that we could not have a closing unless the check was from a British Clearing Bank. A cashier’s check on the Bank of America was not good enough. What would happen if they went broke over the weekend and the check did not clear on Monday? I suggested that we close “subject” to the check clearing on Monday. My very thorough attorney then spent the next 20 minutes explaining that a closing “subject” to anything was not a closing. I enjoyed the lecture on the finer points of British jurisprudence, as my spirits became as damp as my suit.

I agreed with everyone in sight, apologized for the Bank of America, admitted that I was disastrously ignorant, and eventually we sort of “closed.” A little groveling sometimes goes a long way. The Bank of America did not go bust over the weekend, World War III did not break out and I officially owned the company on Monday.

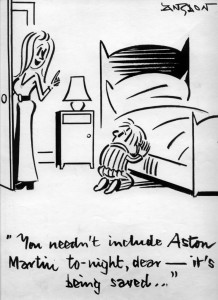

As far as I was concerned I owned it on Friday. The sensation was strange. I was glad the six months were over. I had no real plan for the next six months. I felt more empty than elated. The following morning The Daily Mail ran a wonderful cartoon showing a small boy praying beside his bed with his mother standing behind him. The caption read, “You needn’t include Aston Martin tonight dear, it’s being saved.” What was I going to do to live up to the expectations of the small boys of England and beyond? It was a daunting challenge. I felt thoroughly daunted.

That Friday evening I drove back to Newport Pagnell where 8 or 10 of us had dinner. Fred Hartley, David Flynt (Production Manager) and other key members of the suddenly formed resurrection team were there. I did not know them well. There hadn’t been the time or the inclination to get together before the acquisition was complete. With the aid of a few bottles of Champagne and a few stronger drinks I began to cheer up. It wasn’t exactly a victory celebration, but we were all happier than we had been on Thursday. I looked around the room and began to believe that the team in the room could somehow pull it all back together. And they did.

I returned to the States where, in the following week, I also acquired a controlling interest in the Advent Corporation, a publicly owned, struggling, but well known manufacturer of audio components and large screen projection televisions. Suddenly, I found myself in the rescuing business on a grand scale. In retrospect I should have limited myself to one damsel in distress. Advent took a lot of time and is another story entirely.

I still needed a fully active partner at Aston. George Minden was off in Canada or Switzerland or the English countryside. His wife Pamela was attempting to get him to retire and occasionally she succeeded. I needed someone who would be there all the time. Of all the people who I had talked with that spring, one individual stood out. I called Alan Curtis. His teenage son, who was an Aston fanatic, answered the phone and in a reverential tone said to his father “Peter Sprague is on the phone.” Alan later said that he agreed to join in the effort because he couldn’t disappoint his son. Alan had been in construction and loved airplanes. He flew the only British Bulldog aerobatic airplane in private hands. He had earlier insisted that he had no interest in cars and would not invest.

He was the right man for the job. I asked him to come and visit the factory before he turned me down again. He agreed. The evening before the visit we had dinner at the Dorchester. By good fortune I had ordered a Chateau Becheville Bordeaux, which turned out to be his favorite wine. I ordered my lamb rare, Alan had his well done. I reached over the table to sample a burnt specimen. This isn’t done in England. Alan later admitted that he decided to become my partner because it was unlikely that anyone else would.

The next day we went to Newport Pagnell. Once more I walked through the empty factory, which this time I owned. The gloomy dead factory once again worked its magic. Alan signed on and agreed to invest and join the Board. The rest of this story involves Alan at least as much as it involves me. I had a partner and a new friend. I needed both.

Ironically the press had already speculated that there was a “secret” English partner behind our original purchase of the company. There was no “secret partner” but I had felt no reason to deny the existence of a British element in the purchase. Alan stepped into previously empty shoes.

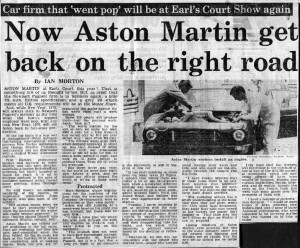

Slowly we began to restart the company. Fred Hartley led the effort. We had an auction of the exotic bits and pieces that were lying around. Members of the Aston Martin Owners club showed up and bought £17,000 worth of stuff. We used the money to buy drafting tables and restart the engineering team. We began to complete the last few cars on the line. They were finished in the Service Department. Slowly, laid-off members of the factory team began to rejoin the company.

As we started to put the company back together we put more and more trust in the workforce, the men and women who actually built the cars on the line. Former “managers” with British public school educations and unclear job descriptions were simply not rehired. Our extraordinary production manager, David Flynt, went to the workforce and stated the obvious. If we keep operating as we had in the past we will go out of business again. We had to make changes and become more efficient.

One of my favorite examples of the inefficiency of having a labor force that does not communicate was the case of the ‘excess bracket.’ We found that one craftsman with great care was welding a bracket on to the frame. An equally fine craftsman was removing the same bracket with equal care three stages down the production line, about 40 feet away. They had tea together every day. No one knew what the bracket had ever been used for. In the old way of doing things there was no motivation to change this procedure because eventually it might lead to a loss of employment for one or both of the two people involved.

David Flynt changed this and the fundamental mindset behind it. In the first six months there were over 2300 engineering change orders, most of them initiated by the workforce. Years later at an event at Silverstone race circuit organized by Alan Curtis where all the employees and their families had a picnic and everyone got to drive in an Aston (most for the first time), one of the employees was interviewed by ITV television. When asked what he thought, he stated, “It used to be them and us – now its us.” The change began when the factory restarted. The company picnic was on a Wednesday. Alan asked everyone if they could make the same number of cars that week in four days that normally took five days. They did and it was a great success.

We had an interesting relationship with the auto workers’ union. We were never sure that we would survive and agreed with the Aston workforce that they should stay in the union and pay their dues. However, Alan Curtis pointed out to the union that the problems of the English automotive industry were different than our problems and could we please be left on the sidelines while the major battles took place. They agreed and occasionally the local union head would call other union bosses to ask that they help us. We contributed a case of Scotch on an annual basis to thank them for their understanding.

Around 1978 there was a major strike at Lucas, our major source of electrical and lighting parts. Lucas was often unkindly referred to as the “Prince of Darkness.” We had few parts on hand and if we could not continue to be supplied we would have had to cease production in 2-3 weeks. Alan, as usual, took direct action. He drove up to Lucas in a new convertible V8 with the top down. When he arrived at the door there were 100 or so pickets with the usual paraphernalia of corporate strife. Alan introduced himself. They asked him what he was there for. Alan replied that Aston needed two weeks supply of parts. They opened the gates, then Alan filled the boot and back seat with what we needed and drove off. The parting words of the gang at the gate were, “See you back in a fortnight Guv’nor.” We survived.

In general I always had the feeling that almost everyone we dealt with wanted to see us continue to survive. There were a lot of Aston enthusiasts who could not afford to buy a car but had a sense of ownership because they were personally involved.

Over the next few years it became crystal clear that the greatest asset at Aston never made the receiver’s balance sheet. The men and women were extraordinary – driven away from production lines and towards craftsmanship by their intelligence and curiosity. I would have guessed that their IQs would have gotten most of the employees into a good university in a more democratic world.

We expanded our Board of Directors. In addition to Alan Curtis and George Minden and myself we were joined by a Dennis Flather. Dennis had made his industrial fortune in the steel business in Sheffield. We had been getting a lot of small donations from children who would send a few pence or occasionally a pound or two. Dennis sent a check for £50,000 with the note that we would probably need it. Neither Alan nor I had ever met Dennis. We called him up and arranged to meet him at the factory and have lunch.

We discovered that Dennis was the ultimate automobile and Aston Martin enthusiast. He had bought his first Aston Martin, a 1_-litre Second Series two-seater in 1933. (Ironically this car was a replacement for a 2-litre Lagonda.) Since that time Dennis had owned eight further Astons including a DB4, a DB5 and a very early fuel injected V8. He was the first Chairman of BRM and founder of the British Trials and Rally Drivers Association and was still the President of that organization.

To further gild his automotive resume he owned the oldest surviving British car in the world, an 1897 Daimler that he regularly drove in the London to Brighton run.

We cashed his check and asked him to join the Board. He cared deeply about the company and had the kind of stalwart backbone that was necessary at that stage of our revival. We always knew that we could rely on Dennis when the going got tough. He had strong opinions about practically everything and he stated them often. He wasn’t always right, but he was there when we needed him.

In October 1975, much to everyone’s surprise we had a stand at the Earl’s Court Motor Show. We arrived with three cars. One of them was a four door V8 that carried the Lagonda name. There were only 7 ever built. The ever-vigilant press immediately pointed out that we had abandoned the Aston tradition of numerous beautiful girls surrounding the cars. David Brown had in the past devoted considerable effort to extensively and intensively interviewing candidates. We didn’t have the time or the money. I was asked by the BBC morning TV show where the beautiful girls were. I commented to their audience that I probably liked beautiful women as much as David Brown but that “I would rather take a lovely lady to dinner than drape her over a car.” We survived the automobile show and they generously gave us the Best Paint Award. Most people never expected to see us again. They were wrong.

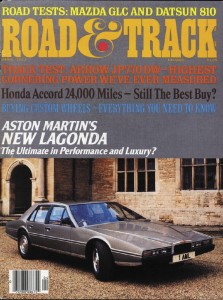

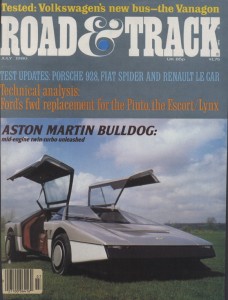

A few weeks after the 1975 Earl’s Court Motor show we began to discuss the future. As a team we had only begun working together for three or four months. We knew that we needed a new model. One obvious choice was to put a new body on the V8 chassis. The existing body design had been around in one form or another since the introduction of the DBS in 1967 and was getting tired.

Moreover, the V8 chassis had too many separate parts and was very expensive to build. Michael Loasby, age 37, who had just rejoined the company as head of engineering, believed he could develop a much-improved chassis that would be less costly to produce.

We then debated whether we should create a brand new coupe to replace the V8 or revive the Lagonda marque around a four-door car. A major concern was that if anyone learned that we were building a new two-door to replace the V8, the market would stop buying the existing model while they waited for the new one. In the interim we could go out of business. I remembered the fate of the Osborne computer company, which had just failed, en route to the future. They had announced a new model months before they could produce it. Everyone waited for the new and ignored the old. The company ran out of sales and cash.

Later that fall we had another meeting for a presentation by William Towns. He produced a drawing of a spectacularly radical four-door design. He has been quietly dreaming up the design on his own over the previous two or three years. We decided to go for it. I believe that the decision was made in a day. There was no dissension. The four company directors all felt that we wanted to own the car in William’s drawings. We wouldn’t ever be able to drive it if we didn’t build it. Thus the Lagonda was conceived. We had a little over nine months until the next motor show, and we had 11 exceptional engineers. After all, even more complex and miraculous organisms had been completed in 9 months. We decided to keep the whole project a secret.

I have been asked many times whether we had done any market research, was there a detailed budget, and what gave us the confidence that we could do it? Basically we looked at William Towns’ extraordinary drawings, and we asked Mike Loasby if he and his team could build it. They said “yes.” We had confidence in the team.

I have great faith in the power of individuals to form a team and accomplish projects at which large corporations routinely fail. Every stage of microelectronic component development has spawned new companies and reshaped the computer industry. The invention of the transistor combined with $70,000 led to the formation of Digital Equipment. The integrated circuit combined with $750,000 led to the startup of Data General. The development of the microprocessor led to the launch of Apple Computer and a number of other personal computer companies.

Lockheed’s “skunk works” developed the extraordinary spy planes of the cold war including the U2 and SR71. Again it was a small unencumbered team with a clear mission and minimal bureaucracy. Aston developed its own skunk works with an exceptional esprit de corps and a belief that they could accomplish their goals with very limited resources.

As the Lagonda began to take form I added my own special contribution – related to my background in the world of microelectronics. The car looked amazingly modern, why not add an all-electronic, computer-based information and control system and really join the 20th Century? It was an excellent idea – but ultimately about 15 – 20 years ahead of its time.

Mike Loasby visited National Semiconductor in California and became enamored with the touch sensitive switches in the elevators. Mike found a company in England making touch switches called Fotherby Willis. Shortly after we committed to work with them, Fotherby Willis announced that they were in serious financial difficulty. This added to the pressure. Today Mike proclaims the touch switches as a “totally bad idea.”

At the time microprocessors were just starting to make a major impact. We would lead the way with the latest of everything. We gave the job of integration to the Cranfield College of Aeronautics, as Alan Curtis was already working with another part of Cranfield to develop a new aerobatic aircraft for international competitions.

The micro computer we selected was an IMP-16 printed circuit card from National Semiconductor. It cost about $1400. All the displays would be coordinated through a central box. The computer capability contained therein was but a tiny fraction of the capacity of a Palm Pilot today. We were programming this at about the time Apple was introducing its first computer. This led to more than a few complications that I will discuss later on. Among other things, we learned that the automotive environment is much more difficult than that of a modern military aircraft. Everything is supposed to work immediately at temperatures from -30F to +140F.

In early 1976 it became clear that we would have to make further changes in management. George Minden was only intermittently very active as a director. He had a real design sense and a passion for detail, and was focused on the Lagonda. However, when he wasn’t available, decisions had to be made that could not be reversed. He was not around enough or perhaps he was around too much – in either case it was not working. Fred Hartley was struggling with the wide range of responsibilities we had given him as managing director. We had an off-site board meeting at the Dorchester Hotel in London. Alan Curtis agreed to take on the job of fulltime Managing Director. Alan continued to fly his Bulldog aerobatic plane to Cranfield. He completed the remaining 15 minutes of his commute in his battered, wooden sided, Morris Minor Traveler estate car. Alan immediately began to make changes in the factory. He also became a very effective salesman for the company. He worked hard at the job and I believe that he almost always enjoyed it.

Under William Willson the company had not kept up with the safety and pollution requirements of the US and Japan. We needed those markets to survive and began to re-qualify. Despite our production of less than 250 cars a year we had to meet the same requirements in England and the common market countries, Switzerland, the US and Japan, as Toyota and General Motors. We had only a 1-man team led by David Orchard to accomplish the nearly impossible. General Motors probably had more people working on these issues than Aston had employees.

Using an export finance scheme originally developed by Tony Benn, the left wing Parliamentarian to help Meriden Motorcycle, we were able to get export financing for 40 cars that we shipped to our wholly owned subsidiary in the US. Under the terms of the financing the cars were supposed to be saleable in the US. We had a small problem that they had not yet met the American EPA (Environmental Protection Agency) certification.

We were assured by engineering that meeting the US requirements would be a piece of cake. We had six months before time and the financing ran out. We failed the six-hour endurance drive around an oval track in Ann Arbor, Michigan twice. With two weeks left, the piece of cake was getting stale.

This became a typical Aston story. The night after the second failure the two Aston engineers who were with the car in Ann Arbor were easing their frustration with a few beers. Next to them at the bar was a 19-year-old driver who coincidentally had been driving the test Aston that day. He worked for the EPA.

The engineers introduced themselves. The driver began to express his opinion of Aston Martin Lagonda in forceful terms: “You cheap bastards, if you want me to drive reliably and steadily around the same boring oval for six hours the least you can do is put in a music system.” We had shipped a stripped down car without a radio. The engineers called me in Lenox. They were out of money. I wired cash through Western Union. The engineers bought and installed an 8-track cartridge player. The driver loaded his own cartridges. Three days later we passed the test. The driver was happy, and we were happy. New and improved carburetor jets were sent over and fitted to the cars that were in storage. We sold the cars, paid the loan, and did not go directly to jail. We had dodged another bullet and our luck had held.

I began traveling to England about once a month for a week. This was an improvement from 1975 when I had made 17 transatlantic roundtrips. In late 1977 I took one of the first trips on Concorde and continued to use it occasionally. Unfortunately this was before the airlines introduced frequent traveler discounts. On my first trip I remember noticing that there were a remarkable number of silver haired gentlemen who seemed to be traveling with their “nieces.” (There were some very nice nieces indeed.).

A senior flight attendant of the schoolmarm persuasion explained the emergency procedures. “In the unlikely event of a water landing please locate your life preservers under the seat. Do not inflate them until you have exited the aircraft. There is a whistle attached to the life preserver. If you find that you are in the water and have not located the raft, blow smartly on your whistle.” I fly a Piper Supercub, a two seat tail dragger. I knew that in the unlikely event of a water landing in a Concorde we would hit the water going about 180 mph. and would mechanically explode on impact. In the even more unlikely event that I would end up in 34-degree water surrounded by ice floes in the North Atlantic it seemed clear that blowing smartly or dumbly on my whistle would probably not make a lot of difference during the remaining minutes of my life. I returned to the vodka and caviar and decided to forget about it, read a good book and admired the nieces.

The frequent transatlantic trips led to many interesting conversations. My seatmate on one trip, a scion of the Johnson & Johnson Company, mentioned that he had a four horse carriage with the requisite four horses in the baggage compartment below. This redefined in my mind the concept of excess baggage. He also had a full support team in the back of the 747. It was my introduction to International Four in Hand driving competitions. It occurred to me at the time that there might be even quicker ways to spend a lot of money than investing in horseless carriages.

On another trip, exhausted from a late night in London, while en route to New York I was ushered up the circular staircase on a Pan Am 747 for lunch. For a year or two they had installed a small restaurant for the First Class passengers. Linen, crystal, and silver – all that was necessary to remind the passengers that they had had the same service on the old Flying Boats forty years before. I was alone and seated at a table for four, soon to be joined by a couple that did not look like those in the Pan Am brochure. The girl was in a skintight leather minidress that might have been a size or two smaller than she was. She was in her late teens with the stringy hair and the slightly spacey look of a rock groupie. This was appropriate because the guy she was with had on a similar outfit that I don’t remember as well. He was in fact a “rock musician.” He had played a concert at Wembley the night before with the band opening for the Rolling Stones.

During the course of an excellent meal all my first impressions went off to the place in your brain where your prejudices die. They were both delightful. The band was The Eagles, about whom I knew little and the guy was one of its two founders, Don Henley. We had lots of time and I asked him how he had put the band together. He said that he had spent six months before forming the group researching, the “psychodynamics of why rock groups fall apart.” His father had been an automotive executive. We talked about cars and life in general. I had certainly found a potential customer. It was a memorable occasion.

Most trips were less interesting and perhaps the most comfortable were those when the plane was mostly empty and I could stretch out in three or four seats in Economy Class.

My housing situation had improved dramatically. In 1960 Tjasa and I had met Robin Tavistock and Henrietta Tiarks in Cambridge, Massachusetts through a mutual friend, Chuck Downer. We were all students. Robin had preceded me as a student at Le Rosey in Switzerland, an international school that had had such illustrious alumni as the Aga Khan, the Shah of Iran, and Prince Rainier. I used to comment that it was a male finishing school that took two years to finish you. I was there for one year.

Robin and Henrietta later became Lord and Lady Tavistock. Their wedding made the cover of Life Magazine. In 1975 they had a home near the Aston factory called Woburn Abbey comfortably situated on 12,000 acres.

Tjasa and I were invited to lunch at Woburn. Henrietta was bottle-feeding an orphaned tiger cub and breast-feeding her third son James. With her wonderfully open and wry view of the world she commented that it might have been easier to breast-feed the tiger as her nanny refused to have anything to do with the animal. Subsequently the tiger was named “Tjasa” and ended up as a happy resident of their animal park. I was invited to stay at Woburn on future visits and ended up as a happy and regular resident of the Abbey. On weekdays a few thousand visitors would arrive after 9 AM and would leave before 5 PM. I would leave earlier and return later. The evening drive through the game park to the Abbey was magical.

The friendship of the Tavistocks made an enormous difference in the quality of my life. They were enthusiastic and creative supporters of Aston and I loved the time that I stayed with them. Things were looking up from my days at the Swan Revived. Now I could travel from a “stately factory” to a “stately home,” just some eight miles away.

Back at the factory we were producing four to five cars a week and paying our bills with difficulty. We maintained the myth that we were completely sold out for a year. Otherwise we feared that no would have felt the need to buy a car. We needed the world market.

We finally re-qualified to sell our cars in Japan. As usual this wasn’t easy. The bureaucratic “official representative” of all foreign carmakers in Japan was chosen not by the car importers but by the Japanese government. If I remember him correctly he was close to being an octogenarian and had been forgetting the English language ever since he presumably learned it in Coventry in 1936.

One of the tests required was that we place a four inch board covered by a nylon stocking two inches from the end of the exhaust pipe while the engine ticked over at 1500 rpm – for two minutes. If the stocking burst into flame or melted we would be required to redesign the exhaust system. Presumably this was to protect Japanese women from spontaneous combustion if they found themselves with a stocking clad, wooden leg lingering behind an Aston. But we eventually passed. At least we didn’t have to crash test the car. All that hand hammered metal crunching a concrete block! That was a requirement in both the US and Britain.

The Japanese drive on the left, with the steering wheel on the right. A reasonable English approach, which leaves your sword arm free when defending your car against the infidels. However, the Japanese insisted that we ship cars with the wheel on the left. This was to make sure that people who saw the car would know that it was an exotic import.

Aston had sent over an English mechanic, Dennis Nursey, to Tokyo where he promptly became attached to a Japanese girl and stayed. He reported that there was a James Bond tape in every car that came in for maintenance. They needed the panache of James Bond to put the extra four feet of metal into the onrushing traffic to see if they could pass. On the other hand, most Tokyo traffic didn’t allow the driver to get out of first gear.

In 1974-75 Dennis worked with Eastern Motors, the Japanese Aston distributor. He heard about the collapse of Aston on Japanese radio. No one had informed him that the company he worked for was no longer in business. He returned to Newport Pagnell, where it felt like a ghost town. At one point he met with William Willson who told him that he did not want to sell the company to anyone. Dennis was under the impression that if Mr. Willson couldn’t have the company nobody else could.

In late 1975 Dennis rejoined as a Service Engineer. Chubuyashima took over the distribution from Eastern Motors and ordered 40 cars a year for 1976 and 1977. Aston had been selling 8-12 cars a year in Japan. It was a brave order and very helpful. They still had a large inventory in 1978.

Around 1978 I flew to England for a critically important lunch whose purpose I have forgotten, although I remember that the lunch was at the Waterside restaurant near the airport and was excellent. So was the wine. I then got back on another 747 and flew to Tokyo via Anchorage. For an extra hundred dollars I got a bed in a small curtained-off room upstairs. There was another bed in the space – empty. The application of a small amount of imagination conjured up potential occupants. The stewardesses didn’t make the cut. The conjuring interfered with sleeping. It seemed a lamentable waste of space.

Despite the bed I arrived exhausted. I was there to give a talk to the Aston Martin Owners Club of Japan. En route I calculated that between California, NY, England, Iran and Asia I was personally averaging over 40 mph 24 hours a day, month in and month out. It is sometimes easy to confuse motion with progress.

About 150 people showed up for the Aston dinner. I told stories which suffered dismally in translation. I had been to Japan many times before. This group was different. They had humor and enthusiasm and strong independent personalities. They were men and a few women who broke with Japanese tradition and stood out in a crowd. They were not bureaucrats from large organizations. Most were independent entrepreneurs. One gentleman had a chain of restaurants; another a chain of funeral homes. Hopefully one did not serve occasionally lethal puffer fish and provide customers to the other.

They had built their own businesses and felt that they should reward themselves. They did not need permission. They deserved it. Their reward was an Aston. In many ways they were like Aston owners around the world, with a strong independent streak. They appeared to enjoy life and had a sense of humor. I wished that I had the opportunity to spend more time with them. It was the best group I have ever met with in Japan.

The Japanese loved the cars and used to apologize if they broke down. There was one notable exception. Dennis recalls one Japanese owner who lived near the top of a mountain. His V8 had brake trouble and the engine kept cutting out. A new ignition unit had been fitted and had failed. Dennis and a representative from our distributor visited the owner who came storming out wielding an unsheathed Samurai sword. It was obvious from his anger that he intended to impale the distributor rep on the spot. However at the last moment he saw Dennis and stopped. Two weeks later he had a replacement car.

More typical was the customer who asked Dennis to visit him to service his car. Dennis never saw the car. The customer took him night clubbing for days on end.

In 1979 we replaced Chubuyashima with Mitsui. Our potential sales in Japan could be completely lost in Mitsui’s multi billion-dollar balance sheet. But we were Aston Martin and the James Bond connection was not lost on Mitsui.

Alan Curtis, who negotiated the deal, was treated to a lavish launch party with hundreds of guests. The dinner was on a Friday evening. Alan was their guest for the weekend. From the stories I heard it must have been a fabulous weekend. I will leave it to Alan fill in the fable.

Alan dealt with Japan. I had the pleasure of being responsible for Hong Kong. Our dealer there was Sir (later Lord) Lawrence Kadoorie. Sir Lawrence and his brother Horace owned the Peninsula Hotel Group, one third of the HK – Kowloon tunnel, controlling shares in the China Light and Power Company, and jade and ivory collections that were among the top five in the world. The Kadoorie family have always made the short lists of billionaires. Sir Lawrence bought one new Aston a year. My job was to convince him that one car made him a valued customer but that it would take more than one car to move him into the distinguished ranks of Aston dealers.

Sir Lawrence’s son Michael had also been a schoolmate at Le Rosey, so I had the good fortune to have known the family since the early 60s. I would fly out to their estate piloted by Michael in his helicopter and we would have pleasant discussions concerning his failure as a car dealer. These conversations lasted five minutes. The rest of the time I spent with Sir Lawrence, his wife Rachel and his brother Horace in wide ranging conversations that enlarged my view of the world. Michael kept suggesting that I do something sporting, for instance tennis, water skiing or go-karts. Staying equal to the conversation was sporting enough. Eventually our sales in Hong Kong soared to two or three cars a year. They were wonderful people with an extraordinary family history. They had left Iraq during WWII, crossed Russia to Shanghai and eventually escaped from Shanghai when the Communists arrived. I always looked forward to visiting Hong Kong. Aston marketing opportunities were a good excuse.

We had a worldwide network of dealers. Alan kept them all involved and interested. They kept us alive.

In the States, Morris Hallowell took on the responsibility for distribution and we opened a retail store in Greenwich, Connecticut. Rex Woodgate eventually returned to Newport Pagnell where his great technical skills and knowledge were devoted to special projects. The location we chose is still an important Aston dealership now known as Miller Motorcars.

The Lagonda was beginning to take extraordinary shape. By now we had 17 engineers, most of whom were working on the project. The good news was that the car was not designed by a committee. William Towns was responsible for the entire design, inside and out. The result was a striking piece of mobile sculpture. We had long discussions over such questions as whether the car should have a “Mascot” like the Rolls Royce Silver Lady to define the front end of the car. The Lagonda mascot was developed and nicknamed “the Gunsight.” In most of our discussions William Towns prevailed. The Gunsight did not make the final cut for production models. I like to think that the purity of William’s form was perhaps based on his passion for singing Bach Madrigals. The Lagonda looks as modern today as in did 25 years ago.

I recently learned that GM was beginning to take design more seriously in the new Millennium and had decided that their three different engine dipsticks had to have a common look. Someone must have risen to the exalted rank of chief dipstick designer and led a team of lesser designers in quest for the perfect homologated dipstick design. We didn’t have any dipstick designers but we were fortunate enough to have Mike Loasby and William Towns.

Early on we had built a seating “buck” to evaluate the interior space. Fred Hartley, Alan Curtis, George Minden and I sat in various combinations and permutations in the buck. Fred was basically of my size and bulk, Alan and George were more compact. Somehow we all sat comfortably. I am still not sure that the buck we sat in ever had much to do with the interior size of the eventual prototype car. Mike Loasby claims that it simply became compressed by thicker seats, more insulation, etc.

So, typical of English sports cars the back seats were cramped. Unfortunately it was a four-door car with a moon roof in back and the possibility of a chauffeur in front. I am over 6’2″ and couldn’t quite fit in back. One critical wag commented that we had managed to build the first two-seat, two-passenger, four-door car.

I was pleased to learn as we went along that my American nationality was not entirely inappropriate to the revival of the Lagonda marque. The first Lagonda had been built by Wilbur Gunn, a failed American opera singer who had first built steamboats to run on the Thames. His first automobile had been named after “Lagonda Creek” in Springfield, Ohio, now called “Buck’s Creek.” The word Lagonda was an iteration of “swift running” in the Shawnee Indian dialect. The original Indian word had been slightly corrupted to Lagonda by French settlers in 1796. Certainly William Towns’ design lived up to the image of “swift running.”

The nine months our team had to get the car ready for the 1976 Earl’s Court Motor Show seemed enough time considering that it was about the same length of time that it took for other designers and craftsman to build the first Spitfire during WWII. We came very close. There was a great deal of improvising. The pop-up radio popped up with the aid of a mousetrap mechanism that had been found at the last moment and the lid of the box between the seats used a hinge that was taken off a toolbox that was conveniently nearby. Eileen Thorley who worked in the trim shop recalls that they worked overtime to get the Lagonda ready for the motor show “We were always the last to leave the factory. One day I worked until 2AM, and on my walking up Tickford Street a policeman stopped me and asked where I had been out at that time of night. I told him and he didn’t believe me. I dread to think what he thought I had been up to.” Lots of people worked very hard.

Two weeks before the Motor Show we had a special press preview. Our secrecy was such that there was not even a rumor that we were doing anything radically new. Alan arranged for a lunch at the Bell Inn in Aston Clinton, near the famous hill climb that gave Aston Martin its name. Lionel Martin had won the hillclimb there with his car and it became known as the Aston Martin. There were about 120 people at the lunch. Geoff Courtney, our creative PR genius had rounded up the British motoring press, who while doubtful that we would produce any real news were confident that they would have a very good meal while enjoying each others company. Geoff also rounded up a number of members of the Lagonda Club who brought with them a beautiful selection of mostly prewar Lagondas. Douglas Bader, the legless Spitfire ace was there standing tall. I had read his book Reach For The Sky years before and never expected to have the luck and honor to meet him. All the Aston directors were there along with a number of the men and women from the Works who had been present at the creation. My wife and children flew over for the occasion. I was thrilled, proud, and excited.

The curtain was pulled back, and you could hear the intake of breath. Nobody expected what the team had accomplished. Resplendent in silver the car glistened like a jewel under the lights. We had kept the secret and it had been worth keeping.

As the show was a “preview,” we tried to embargo the news until the morning of the Motor Show. We admitted to the press that the car was not a “runner.” It lacked a transmission, but the displays and most of the rest worked. The press agreed to restrain themselves until the Motor Show opened.

The BBC broke the embargo on the evening before the Motor Show. We expected they would broadcast the film they had taken on the morning of the show. Instead, they showed the car traveling gently through a section of seductive English countryside. The rest of the press was furious. Not only had we not enforced the embargo but we had lied to them about the car. It obviously ran despite our assertion that it didn’t. We assured them that despite the evidence to the contrary the car did not run.

The truth was that we had taken the car out on a low loader (flatbed trailer) to the top of a pristine hill somewhere near the Works. The BBC placed some construction blocks into the boot to compensate for the weight of the missing transmission and had then filmed the car as it rolled gently downhill through the countryside, complete with driver. It looked great on the evening television even if they had scooped the rest of the press by a few hours. We apologized profusely to all and sundry.

Motor Show day finally dawned. The Lagonda was on a platform under spotlights. It deserved its limelight. I believe it is fair to say that we stole the show. Prime Minister James Callaghan sat in it and Colin Chapman of Lotus brought over his chief engineer Mike Kimberley to have a look and asked him why Lotus couldn’t have the same exciting instrumentation.

The high moment of the day came when a smiling 60+ year old American came by and complimented the car. He said “We tried to make it shear – but you made it shearer.” I did not know who he was or what he was talking about and I knew little of the language of automotive design. A BBC reporter recognized him and asked if he would say that for attribution. He said it over again but changed the introduction. “It is a magnificent achievement, we tried to make the new Cadillac shear but they made it shearer.” The visitor was William Mitchell, the legendary head of General Motors Design. His generous comments resonated all over England.

The press photographed it, TV filmed it and everybody wrote about it. The notices were sensational. It looked like the Aston show might enjoy a longer run than expected.

The stand was mobbed. The beautiful girls from the neighboring stands came over to ogle the car in a strange reversal of roles. We even had our own gorgeous 16 year old girl on the stand, Yvonne Cravens, who had voluntarily attached herself to the festivities and showed up in a lot of photographs wearing a large black hat and looking smashing. I thought that she was at least 18. James Bond himself would have been impressed with the turnout.

It may not have been reflected in our balance sheet, but as far as the public was concerned, Aston was back in business. We were back on the front pages all over the world. The team at Aston had risen to the occasion and deserved the applause. Somehow I was reminded of the Eliza Doolittle scene after her coming out ball in My Fair Lady. It was a triumph for everyone involved. I felt like singing. Fortunately I didn’t. We did break open a few bottles of self-congratulatory Champagne.

More importantly we received 76 orders at the 1976 Motor Show, mostly for Lagondas. Nick Mee and Colin Thew remember driving from embassy to embassy collecting deposit checks.

Eventually we sobered up and went back to work. The car still wasn’t a runner. We had a backlog of customers from around the world and a non-working prototype. One Spitfire would not have won the Battle of Britain. We needed to start making Lagondas.

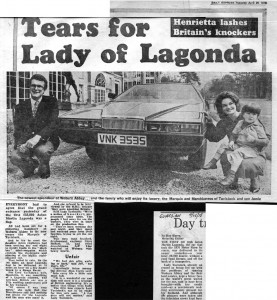

In 1977, when we were ready to deliver the first Lagonda, the delivery was not going to be a secret. We told the press that we had a mystery customer and would release the first car at a midday event at Woburn Abbey. We had been very optimistic about our completion schedule. It is easier to build a prototype than to build production automobiles on a manufacturing line.

The night before the delivery I visited the factory with Lord Tavistock at about 3AM. There were 14 people still working on the car. Six or seven of them had their hands in the engine compartment. I commented that it looked like they were taking an appendix out. They replied the situation was worse than that – they were trying to put an appendix back in.

It turns out that National Semiconductor’s IMP-16 computer board had developed a glitch, or a bug, or whatever. It didn’t work and therefore the car would not run. Back then, we were not surrounded by teen age computer wizards.

As the day dawned it became clear that we were in trouble. The Lagonda was supposed to drive to Woburn Abbey at 11 am. We had invited the press – motoring and otherwise. All the TV channels were planning to send crews. The food and drinks in the Sculpture Gallery were already being laid out. People were on their way. Expectations were high. The car was low. We seriously considered canceling the event, but by then that was impossible.

Plan B was to hope for divine intervention before 11AM. This did not occur. Plan C was to send the car to Woburn on a low loader again and hope that no one would notice. We opted for plan C.

So the car was towed to Woburn Abbey, which has a magnificent mile long driveway to the front of the house. We tried the back entrance but that didn’t work either. It is hard to smuggle anything as inherently conspicuous as a Lagonda. When the car arrived the press was already there. Our clandestine arrival did not fool anyone. To describe the situation as embarrassing would be to understate the obvious. Alan Curtis looked at me and decided that this would be my turn as Co-Chairman to “Meet the Press.” There were more than 100 people in attendance and the cameras were running.

Our mystery purchaser was Lady Tavistock who had arranged with Diner’s Club to buy the £25,000 car on her credit card and then give the Lagonda to Lord Tavistock in honor of their 25th wedding anniversary.

I stated the obvious. “We goofed” or, more specifically, “I goofed.” I held up the malfunctioning computer circuit board by one fiberboard corner and explained that the computer had packed it in. It had been my bright idea in the first place; the engineers and the factory were innocent. Everything about the car was magnificent with the slight problem that it did not run. It was not the fault of the Aston workforce. It would run the following day.

While the cameras continued to run I pointed out that at least we had answered the question concerning the identity of the mystery purchaser. I stated that our choice of first customer had made a lot of sense. Lord and Lady Tavistock were frankly the only friends I had who could afford the car and lived within walking distance of the factory. That line brought down the house. The crowd laughed with us instead of against us. A great deal of wine was consumed, the lunch was excellent and we waited for the response from the reporters that evening and the following day.

Late that afternoon Lord Tavistock drove one of his functioning cars to the factory to thank the work force. He apologized to the Lagonda team for putting them under such pressure. It was a kind and thoughtful thing to do. One witness remembers that there were tears in the eyes of some of the men.

The Press were remarkably gentle. They were willing to give us another chance. As usual no one wanted to see Aston fail. Even the cartoons were more humorous than barbed.

Henrietta recommended that I get out of town and volunteered that I could stay at their home in Newmarket for a few days of peace and quiet. While in Newmarket she convinced me to invest £5,000 for a half interest in a young colt who was tearing around a hillside on a lovely spring day. The colt should have been called Lagonda. He was truly swift running despite his 1/2 horsepower. Best of all there was nothing electronic about him. We sold him a year later at a profit, a very satisfactory transaction.

The car did run a few days later. We had clearly rushed it too quickly to market. Lord Tavistock handled the situation with great diplomacy, living up to the classic definition of a diplomat: “An honest man sent out to lie for his country.” For the next month we followed the car with a Mini loaded with parts, tools and two mechanics. Given the factory support team it ran reasonably well. Robin drove the car to the London Stock Exchange and about 1/3 of the Members visited the Exchange garage to see the car.

On another occasion Lady Tavistock drove the Lagonda rather quickly down the M1 motorway at about 80-90 mph. A blue light starting blinking in the rear view mirror. After she had stopped a very young policeman came up to the side of the car. “Is this the new Lagonda?” “Yes.” “And aren’t you the Marchioness of Tavistock?” “Yes.” He grinned. “My mate and I were wondering what it was like to drive the new Lagonda.” Henrietta smiled and a few minutes later she was in the passenger seat with the policeman driving down the motorway at over 100 mph, and his mate struggling to keep up in the police car behind. After a while the joyride was over and the policemen departed with the admonishment that Lady Tavistock should drive more slowly in the future.

In a strange way the thoroughly botched introduction worked in our favor. Everybody was pleased to see the car running and the reaction was enthusiasm and occasional applause. Robin commented that when he drove his Rolls Royce he tended to stay away from the curb in parts of London because he could feel a kind of class hostility. With the Lagonda he drove close to the curb so people could enjoy seeing the car. We were not just an expensive car for wealthy aristocrats and rock stars. We had a broader audience of people who were glad to see that a small British company could produce a beautiful car that made people smile.

Kingsley Riding-Felce, who then as now worked in the Works service department remembers driving PUR 106R, a gray Lagonda, down to London and having pedestrians applaud. On one occasion all the passengers on a bus moved to one side for a better look and it almost tilted the bus into an accident. There were thumbs up all around.

Not everyone saw it that way. Years later I was given a copy of a Swedish book edited by Nigel Blundell called Varldens Storsta Misstag, which translated into the “World’s Hundred Greatest Mistakes.” I was in there with a picture of the Lagonda. This dubious distinction was shared with the likes of the Titanic, Columbus looking for a fast way to India, and the cost overruns of the Sydney Opera House. It really wasn’t that bad and I was relieved to discover that no individual was in the book for two of the greatest mistakes. I could look forward to the future with renewed optimism. Fortunately there has not been a second edition.

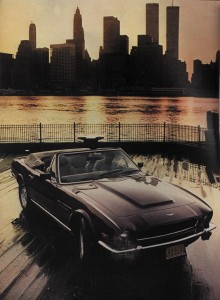

One of the principal reasons that we had committed to the Lagonda project was that the engineering force had cautioned us that it would be very difficult to turn the V8 coupe into a convertible. Our dealer in Beverly Hills, Chick Vandergriff, had assured us that he could sell all the convertibles we could build provided the top was automatic and worked easily. He never did explain to me why there were lots of Mercedes convertibles running around Hollywood with manual tops. I would still wager that the average Aston owner is more robust than his or her Mercedes counterpart.

Alan Curtis informally discussed the possibility of a convertible with Harold Beach, the legendary Aston engineer (and designer of the DB4 chassis), who was helping the factory with a number of special projects. Harold saw no reason why a convertible would not be possible and introduced Alan to George Mosely who had designed the Bentley convertible mechanism. For £5000 and £150 royalty per car George gave us a design, including structural reinforcement of the chassis. The structural parts of the top mechanism were designed to be made in wood, an excellent choice for limited quantity production, both stable and rust free. Harold provided engineering support.

Alan met with the workforce and gave them a challenge. Build one car clandestinely on the production line following the new design. Keep the car covered when it was not being worked on. When completed, we would surprise the engineering group. The design engineers were in a small building across the road from the factory, about 100 feet away. The building was called Olympia and was even less imposing than Sunnyside, the World Headquarters of Aston Martin Lagonda Limited.

Oddly enough there was a strong tradition of building convertibles in Newport Pagnell. The origins of Tickfords go back to the 1820s when they were building gentlemen’s carriages and eventually bread wagons and hearses. In the early 1900s Salmons & Sons pioneered the all-weather coach and subsequently concentrated their resources on building convertible bodies. This led to the Tickford All-Weather Patent Folding Hood that could be raised and lowered with a single handle. Hundreds of saloons of all makes were converted every year with a work force that peaked at 600.

Nigel Shepherd sleuthed a quote from a Tickford Sales Brochure:

“Safeguard your health – Tickfordize.”

“A little experiment to try for yourself. If you doubt the presence of foul air and tasteless, odorless carbon monoxide in your saloon car try this simple experiment next time you make a journey: Place a sound banana on the floor of the car: drive the closed car for a hundred miles or so, and then examine the banana. You will find that is has turned black.”

I have always preferred convertibles but I never thought of the health advantages. Perhaps the hundred miles was over a very bad slow road. Hopefully no one ate the contaminated bananas.

As usual the factory team met the challenge. Over a two-month period they kept the secret and completed the convertible prototype. I happened to be in England at the time. We rolled the car out of the factory. The workforce came out to watch. Alan jumped in the driver’s seat and we drove across the street. Alan leaned on the horn. The engineering group came out from Olympia to check on the commotion. The latches were released, a button was pushed and the top went down. Even better, it also went back up with the push of a button. The “Volante” was re-born and went on to be a great success. The workforce had done it again.

Aston Martin has always had an extraordinary work force. This was not necessarily reflected in their pay packets. The 100 plus skilled craftsmen were paid roughly £60 per week. Semi-skilled workers received £50 and the few unskilled employees were paid £40 per week. The six foremen were paid £80. We were a long way from Henry Ford’s ideal that a Ford car could be purchased by a Ford worker. In our case if a worker saved half his salary they could buy an Aston in 10 – 20 years.

The lead man who cut and fitted the leather interiors with the famous Connolly hides was so good at what he did that one American customer commented about his craftsmanship: “It’s extraordinary, it looks almost like plastic.” Sic Transit Gloria.